I generally dislike anything that starts with "negative", but not this one.

The first part of this article might feel out of place but bear with me. I just want to prove to you that the human brain changes itself according to its environment and why the environment matters so much. If you already are convinced or just want to skip the human brain part, you can skip the first part.

In the second part, I'll explain what ma is, and how it can be used in art and living spaces, and play a helpful role in mental health. I'll try to give examples from the Japanese (and Chinese) culture where the word itself is stemming from.

Adaptation & Maladaptation

Human brains are amazing. One of the most compelling qualities that makes them so amazing is the continuous adaptation ability to ever-changing requirements of the world around them, also known as neuroplasticity. The human brain can change its functional and structural organization to fit the needs of its environment.

Not all adaptations are beneficial for the human, and this situation is called maladaptive plasticity. For example, The writer's cramp (or the musician's cramp, which is a very similar condition) are thought to be caused by the dysfunctional reorganization of the brain, and they both result with involuntary muscle contractions that fiddles with the fine motor control of the hands. (And this can be reversed by sensory motor retuning, read this article if you're interested.) There are also syndromes that involve sensory information that shouldn't be there, such as the phantom limb syndrome (which is defined as recurring sensations, like tickling, itching, or pain from a limb that is lost), or tinnitus following a hearing loss. What exactly causes these syndromes are still unknown and debated, but dysfunctional cortical reorganization looks like one of the culprits.

However, I must point out that most adaptations are pretty useful. Think of a person that learns anything. It can be a perceptual, a motor or a cognitive skill, or a mixture of these. The best (and the most common) examples are musicians. The ability to create music is a skill that requires motor and cognitive adaptation and is learned by years of practice. (No easy way out!)

What changes in a human's brain when it starts to learn how to use a musical instrument? Its brain starts adapting to this demand by modifying the motor, tactile and auditory regions. There is also a study that suggests music training (especially at a younger age) modifies other regions in the brain that are not closely related to playing a musical instrument, such as verbal memory. Your brain changes with every new skill you learn, and it's not only making new synapses but changing its structure to adapt.

We experience the world around us by tiny receptors, whether it be sensing light, pressure, temperature, or sound, it doesn't matter. We feel the light touch of the wind on our skin, and the heat of another person's body, and the sense of pressure when we are hugging each other. We smell a beautiful flower and hear the birds chirping. Our brains collect all this sensory information and analyze it, and even responds to it if it needs to. In cases of sensory loss (such as blindness, deafness, loss of a limb, etc.), our brain seems to adapt by assigning new functions to the neurons that were responsible for that sensory information. Some studies suggest that this results in enhanced performance on other tasks. A good example of this is blindness, the performance of tactile and auditory tasks in blind individuals is found to be enhanced. It even happens after blindfolding sighted individuals just for a few days. This probably has a very good reason, if you cannot use your eyes, you use other sensory organs to give you information about your environment, and as the synapses in the visual cortex get weaker, synapses in the auditory and tactile cortex get stronger. And synapses influence the neighboring neurons too.

The bottom line is, the existence or nonexistence of things around it changes a human brain. As humans, we fear the word "empty"- a depressed person fears the "empty" feeling that comes occasionally, an artist fears the "empty" canvas, and we all fear the "empty" refrigerator. But if space or the emptiness is not forced to the human but purposefully created by it, it can become an adaptative quality that eventually benefits the person experiencing it. The empty space creates an enhanced experience of whatever is taking the space.

And this article is about the purposeful non-existence of things.

The concept of 'ma', the purposeful emptiness

"Ma" is the Japanese concept of space, which is also referred to as "negative space", "interval" or "gap". Although it is a space, it is not considered to be actually "empty". As it was deliberately, purposefully left as a space, it contributes to that piece as much as the other accompanying elements. The negative spaces allow thoughts, relationships, and functions to exist.

Think of music. The places where no sound exists also contribute to the overall experience of it. Think of a bowl. The reason why it can hold anything in the first place is that it has an empty area inside of it. Essentially houses are tiny closed boxes that are surrounded by walls, but what makes the living space is the empty areas inside of it. Or simply think of this text, how hard would reading this be if there were no spaces between words?

Ma can be reflected in almost anything: If we are talking about humans, it can be personal space or silent gaps in the conversation. Not avoiding the gaps allows things to be intentional. If you talk less, you can mean more. If we're talking about a room, it can be the space between things you own. Not avoiding gaps in your living space can allow you to move and clean more efficiently, and even be more grateful about the things you own.

Empty spaces in art

Ma is crucial for some art forms. Without the negative space, the expression of the feelings the artworks want to relay get lost before reaching the audience.

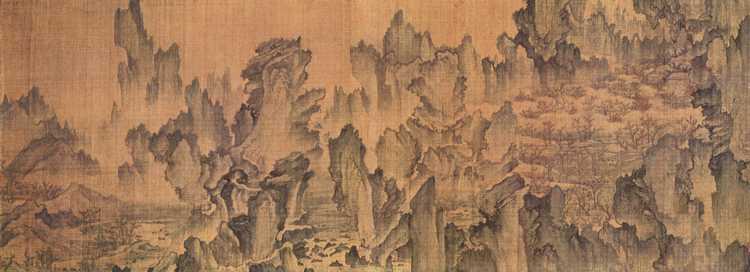

One of the best examples of art forms that use negative space is Sumi-e. Sumi-e is a type of East Asian brush paintings that uses the same black ink in different concentrations, which results in monochrome ink paintings. This brush painting technique is almost 2000 years old, and originally stemmed from China during Tang Dynasty (618–907), and was later introduced to Japan. The earliest practitioners of this art form were Buddhist monks, and this is not very surprising, as the demands of the technique almost completely match the demands of being a Buddhist monk: concentration, calmness, clarity, and simplicity. Both require a tranquil mind.

The artworks are done on rice paper, which is also very appropriate for this art form. As the rice paper is very thin and fragile, the artist has to work with confident brush strokes. There are almost no chances of undoing what has been done "wrong". Every brush stroke has to be intentional, but in a way, the brush also has its own mind, so it can create unexpected textures. This art form doesn't try to reflect or recreate the subject in every detail but aims to capture the spirit of it.

Painting of part of Landscape of the Four Seasons by the monk Tenshō Shūbun from the Muromachi period, showing an idealized Japanese landscape, where man was humble and lived in harmony with nature. This ideal landscape was also depicted in Japanese gardens.

Image Credit: By Tenshō Shūbun - Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7693455

Sometimes the negative space contains calligraphy and the artist's stamp in a beautiful red color, but it is not a must. Check "Landscape" from Sesshū for reference.

Luxuriant Forest among Distant Peaks, by Li Cheng, 10th century. Dimensions are 46.0 x 298.0cm. Collection of the Liaoning Provincial Museum. Dates back to the 10th century, early Northern Song Dynasty.

Image Credit: Li Cheng (c. 917–967), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land, by Ahn Gyeon, 1447.

Image Credit: Ahn Gyeon, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement. Etymologically, it is a combination of two Japanese words, ikeru (which means to have life, to be living, or to arrange) and hana (which means flower). So it can also be translated as "giving life to flowers". Another common aspect of ikebana is minimalism, the pieces are not composed of many elements, but space is used in such a way that gives flowers life and enhances the longevity of their beauty. The space around the flowers is not to be blindly filled but preserved so that it creates balance.

「 The whole universe is contained within a single flower. 」— Toshiro Kawase

An example of Ikebana.

Image Credit: Anna Cicognani, https://unsplash.com/photos/RRl4UPoC-8E

A Japanese Garden is an idealized view of nature. They are layered with rocks, plants, and ponds to create the illusion to be bigger than they are. Everything is not supposed to be seen at once, but step by step discovered. Rocks can symbolize mountains and ponds can symbolize seas. The winding road you take carries you to new landscapes one after another.

「 Though inspired by nature, it is an interpretation rather than a copy; it should appear to be natural, but it is not wild. 」— David and Michigo Young

Early Japanese Gardens resembled Chinese ones, but with time, Japanese Gardens developed their own nature. Chinese gardens were inspired by Chinese landscapes and Japanese ones were inspired by Japanese landscapes, which are pretty different from each other.

Zhangjiajie, Hunan, China. An example of Chinese Landscape.

Image Credit: Joshua Sortino, https://unsplash.com/photos/k4yqev37nNY.

Alpes japoneses (日本アルプス, Nihon Arupusu). An example of Japanese Landscape.

Image Credit: Jezael Melgoza, https://unsplash.com/photos/nM0J7zQ7K4U.

Japanese gardens are also not a single group, for example, the gardens that exist in Buddhist temples are designed to be experienced while seated and are called Zen Gardens. On the other hand, the promenade gardens are designed to be experienced while walking. But some things are common, such as nothing in a Japanese garden is left to chance, and everything in it is purposefully placed, and chosen for a reason. The negative spaces are carefully planned as well.

A spacious Japanese garden, Suizen-ji Jōju-en, near Kumamoto Castle.

Image Credit: 663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

Some studies suggest Japanese Zen Gardens could be used as a non-pharmacological treatment method (in combination with pharmacological treatment methods) in dementia patients to help improve their wellbeing. A study made in 2014 by Goto et al., compared an indoor Japanese Zen garden setting with a Snoezelen room (which is a room filled with multiple pleasant sensory stimuli, such as aromatherapy, calming music, hand massage), by subjecting late-stage dementia patients to both for 15 minutes, twice a week. The stress levels of the subjects were determined by measuring the heart rate and observed behavioral changes. Although I think that the study should be replicated with even more possible settings in a more controlled environment (maybe a completely empty room, an outside garden, or even non-overwhelming gardening activities might have positive effects as well), they did conclude that most late-stage dementia patients preferred to be in the indoor Japanese garden and exhibited a significantly lower heart rate and positive behavioral changes. The same group of scientists did another similar experiment in 2017 (this time on Japanese patients) with three different garden experiences, and came to a similar conclusion.

Although it needs further investigation, there are other studies that suggest the visual aspect of viewing a carefully designed garden, or gardening itself might be beneficial for patients with long-term conditions, such as chronic diseases. And maybe, we should think about designing better hospitals to boost the wellbeing of both the patients and the people working there and increase treatment success. (Maybe. Just maybe.)

Meditation and Mindfulness

Meditation is practicing a set of techniques that promote self-awareness and focused attention while reducing stress. Its roots are dipped in many cultures and religions, especially in Hinduism and Buddhism. There are many ways of doing it, but all of them have the same purpose: to make a person focus on a single thing. So we can simply define it as creating a purposefully empty space in your mind so that you can focus on a single thought. Although there is a misconception about meditation: it is not necessarily cutting off everything and think of nothing - as the human mind is rarely empty and thinking of nothing. You turn down the volume of the outside world, create an empty space, and invite a single thought and give that thought a space to grow.

Mindfulness meditation is one of the most used techniques. Simply put, it is the act of bringing your thought to the present moment, and experiencing the present moment in its full range - feeling the air and clothes touching your skin, or simply smelling and hearing what is actually around you. You are there and you exist in this very moment. You feel that to your bones, and while you don't know the exact reason, you feel grateful to be alive on Earth.

In my opinion, the most important part of both is that they require you to be intentional. You are not letting things happen to you, but taking control of some simple things you can control, and this can calm you in ways you can't imagine. You don't have to sit in front of a lake at 4 AM to experience this. Everybody reaches this state of mind in a different way. I've read about people who practice being at the moment while doing the dishes - trying to do it as quietly as you possibly can, will make every move of your hands intentional, therefore creating a similar experience. I've seen potters and blacksmiths, so immersed in the work they do with their hands that they feel rested even after a very physically intensive job.

In contrast to the old age of the practices themselves, the research on meditation and mindfulness is still young. However, there is data showing that mindfullness meditation might be causing neuroplastic changes in the brain regions that are associated with attention, emotion, and self-awareness, therefore improving one's well-being.

Reduced Environmental Stimulation Therapy (otherwise known as sensory deprivation) is another non-pharmacological technique that works by the intentional reduction of external sensory stimuli. It is another way of creating an empty space in your mind. Although it needs further investigation, there are some studies that suggest sensory deprivation might be inducing a reduction in anxiety and improvement in mood.

Delboeuf illusion

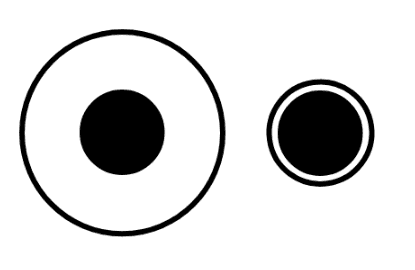

Delboeuf illusion is an optical illusion that creates distortions on the perceived size of a thing by simply creating or omitting an empty area around that thing.

Delboeuf illusion: The left circle is the same size as the right one, but the right circle seems larger.

Image Credit: EricABCAT, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The perception distortion works both ways: a study published in 2012 showed that consumers serve significantly more food on a larger plate, and serve significantly less on a smaller plate when compared to mid-size control plates. Want to fool yourself into eating less or more? Play with space. If you need to consume more, choose larger plates. If you need to consume less, choose smaller plates.

Interesting fact: Some animals are not susceptible to optical illusions such as this. Optical illusions not only depend on the ability to receive visual input but to interpret the incoming sensory data as well. For example, studies on red-footed tortoises and dogs showed that they have no preference for larger portions. But chimpanzees and bearded dragons seem to have a similar susceptibility to this optical illusion as humans. Although it is good to keep in mind that designing and interpreting animal experiments is hard, so our understanding of these animals might change in the future.

Conclusion

The existence of things matters. The non-existence of things also matters. This means, as always, balance is the key.

In this article, I've shared some concepts that embrace and celebrate the negative space. If you start looking, you might see other things that make you think that without the space they provide, they wouldn't be as beautiful or as beneficial as they are now. There are many other things the reader of this article to explore, only if they'd like to.

May the space be with you!

Resources:

- Wikipedia

- Tamura Y, Ueki Y, Lin P, et al. Disordered plasticity in the primary somatosensory cortex in focal hand dystonia. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 3):749-755. doi:10.1093/brain/awn348

- Chan, A., Ho, YC. & Cheung, MC. Music training improves verbal memory. Nature 396, 128 (1998). doi: 10.1038/24075

- Brain to Blame for Musicians' Cramp by Laura Helmuth

- Candia, V., Wienbruch, C., Elbert, T., Rockstroh, B., & Ray, W. (2003). Effective behavioral treatment of focal hand dystonia in musicians alters somatosensory cortical organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 7942–7946.

- Quartarone A, Bagnato S, Rizzo V, Siebner HR, Dattola V, Scalfari A, Morgante F, Battaglia F, Romano M, Girlanda P. Abnormal associative plasticity of the human motor cortex in writer's cramp. Brain. 2003 Dec;126(Pt 12):2586-96. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg273. Epub 2003 Sep 23. PMID: 14506068.

- Pascual-Leone, A., & Hamilton, R. (2001). The metamodal organization of the brain. Progress in Brain Research, 134, 427–445.

- Nava, E., & Röder, B. (2011). Adaptation and maladaptation. Progress in Brain Research, 177–194. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53752-2.00005-9

- Flor, H., Elbert, T., Knecht, S. et al. Phantom-limb pain as a perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization following arm amputation. Nature 375, 482–484 (1995). doi: 10.1038/375482a0

- Goto, S., Kamal, N., Puzio, H., Kobylarz, F., & Herrup, K. (2014). Differential Responses of Individuals with Late-Stage Dementia to Two Novel Environments: A Multimedia Room and an Interior Garden. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 42(3), 985–998. doi:10.3233/jad-131379

- Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Apr;16(4):213-25. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916. Epub 2015 Mar 18. PMID: 25783612.

- Howarth M, Brettle A, Hardman M, et al What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: a scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription BMJ Open 2020;10:e036923. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036923

- Feinstein JS, Khalsa SS, Yeh HW, et al. Examining the short-term anxiolytic and antidepressant effect of Floatation-REST. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0190292. Published 2018 Feb 2. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190292

- Koert Van Ittersum, Brian Wansink, Plate Size and Color Suggestibility: The Delboeuf Illusion’s Bias on Serving and Eating Behavior, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 39, Issue 2, 1 August 2012, Pages 215–228, https://doi.org/10.1086/662615

- Santacà, M., Miletto Petrazzini, M. E., Agrillo, C., & Wilkinson, A. (2019). Can reptiles perceive visual illusions? Delboeuf illusion in red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonaria) and bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 133(4), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000176

- Miletto Petrazzini, M.E., Bisazza, A. & Agrillo, C. Do domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) perceive the Delboeuf illusion?. Anim Cogn 20, 427–434 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-016-1066-2

- Parrish AE, Beran MJ. When less is more: like humans, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) misperceive food amounts based on plate size. Anim Cogn. 2014;17(2):427-434. doi:10.1007/s10071-013-0674-3