If you want to imitate any piece of code in this article, I simply suggest using the mighty Chrome console. You can open it by using the Command + Option + J shortcut in Mac or the Control + Shift + J shortcut in Windows.

⁂ What is in this article?

This article is a long one and it consists of five main sections and their subtitles:

Let’s start by learning how to check the variable types. JavaScript has a simple and very useful operator for this purpose, and that is the typeof operator.

We’ll go through every data type you see in this example, and some more:

typeof 3; // ↪ "number"

typeof "hello"; // ↪ "string"

typeof undefined; // ↪ "undefined"

typeof null; // ↪ "object"

typeof true; // ↪ "boolean"

typeof { name: "cake" }; // ↪ "object"

typeof [1, "cake"]; // ↪ "object"

typeof NaN; // ↪ "number"Operators like typeof, ++, -- and ! are called unary operators because they accept a single value. Operators like >, <, +, -, *, / are called binary operators as they accept two inputs and create a single output.

The data types in JS can be divided into 2 major categories: Primitive and Non-primitive (or Reference).

Primitive data types:

String, Number, Boolean, Null, Undefined, Symbols(ES6), BigInt

What makes primitive values “primitive”?

If we create a variable and link a value to it ( let a = 5), it will be stored in memory. If we create another variable and assign it to the first variable that we created (let b = a), a copy of the first variable is created and copied to the second variable (in memory, the second variable we created will be kept like this: let b = 5).

If you change the value of the first variable (a = 10), the second variable created will still be equal to the initial value of a (b = 5).

Primitive data types are compared by their values:

let a = 5;

let b = 5;

a === b; // true

a = "oh";

b = "oh";

a === b; // true

let c;

let d;

c === d; // truePrimitive data types are considered immutable, which simply means you cannot modify primitive data after it has been created.

Example:

let word = "hello";

word[0] = "y"; // This does not throw an error, but it also does not change anything.

console.log(word); // "hello"Now, let’s talk about all primitive values one by one:

-

1. String:

Strings are just pieces of text. What makes a string a string is the quotation marks around it. It can be double(”…”) or single(’…’) quotes, or backticks(“), it doesn’t matter, but you need to be consistent throughout your code. Don’t mix both.

JS uses 16 bits to encode a single string element. But some characters (such as emojis) are represented with two character positions (2 blocks of 16 bits).

The only arithmetic operator that can be used on strings is +, and it does not add, but it concatenates, which is stitching two pieces of string to each other.

console.log("crazy" + " " + "bird" + " " + "lady"); // prints: crazy bird ladyUsing template literals is a way to make a string hold bindings (or placeholders). If you want to write a string as a template literal, use backticks(“) instead of quotation marks. And when using a placeholder, place the placeholder inside

${}. A very simple example is shown in the next code block. You can nest template strings, and they also can hold stuff like ternary operators. You can even create multiline strings if you ever need to. One downside of it is, it is not supported by IE.Some methods come built-in with every string and they are extremely useful. You can check them from the MDN docs, or writing

String.prototypeto your chrome console, which will return you the String prototype object.👉 Click to view built-in string methods cheatsheet

let color = "yellow"; // -> Template string: console.log(`${color} is the best color`); // Prints: yellow is the best color --------------------------- // -> Strings have indices, and indices always start with 0. They also have a built-in length property. // -> charAt() is a built-in method that gives us the character at a given index. // -> charCodeAt() is the built-in method that gives us the UTF-16 code of the character at a given index. const sentence = "purple is the new yellow"; let index = 3; console.log(`The character at index ${index} is ${sentence.charAt(index)}`); // Prints: The character at index 3 is p` console.log(sentence.length); // prints: 24 console.log(sentence.charCodeAt(index)); // prints: 112 --------------------------- // -> concat() is a built-in method that merges two strings and returns the result as a new string. const str1 = 'taco'; const str2 = 'cat'; const str3 = str1.concat(' vs ', str2); console.log(str3); // prints: taco vs cat console.log(`${str1}, ${str2}`); // prints: taco, cat --------------------------- // -> endsWith() is a method to determine if a string ends with given characters. // -> startsWith() is a method to determine if a string starts with given characters. let str = 'To bee, or not to bee!' console.log(str.endsWith('!')); // true console.log(str.endsWith('not')); // false console.log(str.endsWith('to bee', 21)); // true console.log(str.startsWith('To b')); // true console.log(str.startsWith('To bee', 3)) // false --------------------------- // -> includes() method determines if one string includes another given string. const sentence = "yellow is my favorite color"; const word = "yellow"; console.log(`The "${word}" word ${sentence.includes(word)? "is" : "is not"} in the given sentence.`) // prints: "The "yellow" word is in the given sentence." --------------------------- // -> indexOf() returns the starting index of a given string. It can take a second argument that will make the search start from that given index. // -> lastIndexOf() method does the same thing, but it starts searching from the end of a given string, so it will result in the last occurrence. It takes an optional second argument as an index to start the backward search. // Both of them return -1 if the value is not found, and both of them are case sensitive. const sentence = "a taco cat loves tacos."; const searchTerm = 'taco'; const indexOfFirst = sentence.indexOf(searchTerm); console.log(`The index of the first "${searchTerm}" from the beginning is ${indexOfFirst}.`); // prints: The index of the first "taco" from the beginning is 2. console.log(sentence.indexOf(searchTerm, 3)); // prints: 17 console.log(`The index of the 2nd "${searchTerm}" is ${sentence.indexOf(searchTerm, (indexOfFirst + 1))}.`); // prints: The index of the 2nd "taco" is 17. console.log(sentence.lastIndexOf(searchTerm)); // prints: 17 --------------------------- // -> match() method returns an array with the matching string of a regular expression. const sentence = "Roses are red. Violets are blue."; console.log(sentence.match(/[A-Z]/g)); // prints: ["R", "V"] // Match method either returns an array that contains the elements that match, or null. --------------------------- // -> padEnd() method pads the string with a given string (if needed, repeated), until the resulting string reaches the given length. The padding is applied from the end of the given string. // -> padStart() method does the same, but the padding is applied from the beginning of the given string. const string = "snap peas"; console.log(string.padEnd(12)); // prints: "snap peas " console.log(string.padEnd(24," yes")); // prints: "snap peas yes yes yes ye" console.log(string.padEnd(13," are great")); // prints: "snap peas are" console.log(string.padStart(15,"great ")); // prints: "great snap peas" const year = "1991"; console.log(year.padStart(10,"**/")); // prints: **/**/1991 --------------------------- // -> trim() method removes white spaces from both ends of a given string. // -> trimEnd() method removes white spaces from the end of a given string. // -> trimStart() method removes white spaces from the beginning of a given string. const str = " Greetings! "; console.log(str.trim()); // prints: "Greetings!" console.log(str.trimStart()); // prints: "Greetings! " console.log(str.trimEnd()); // prints: " Greetings!" --------------------------- // -> repeat() method returns a new string with the specified number of copies of a given string. // -> replace() method replaces a given string with another given string, but only the first occurrence of it. // -> replaceAll() method replaces the matches of a given string with all occurrences of another given string. const chirp = 'Chirp. Chirpy chirp. '; const birdSong = chirp.repeat(3); console.log(`This is how the cardinals sing: ${birdSong}`); // prints: "This is how the cardinals sing: Chirp. Chirpy chirp. Chirp. Chirpy chirp. Chirp. Chirpy chirp." console.log(birdSong.replace('chirp', 'chiiiiiiiirp')); // prints: "Chirp. Chirpy chiiiiiiiirp. Chirp. Chirpy chirp. Chirp. Chirpy chirp." console.log(birdSong.replaceAll('chirp', 'chiiiiiiiirp')); // prints: "Chirp. Chirpy chiiiiiiiirp. Chirp. Chirpy chiiiiiiiirp. Chirp. Chirpy chiiiiiiiirp." --------------------------- // -> search() method returns the index of the first occurrence of a match between a given regular expression and a string. If there are no matches, it will return -1. let str = "hello Cookie" let regExpCapitals = /[A-Z]/g let regExpDot = /[.]/g console.log(str.search(regExpCapitals)) // prints 6, which is the index of the first capital letter "C". console.log(str.search(regExpDot)) // prints -1 --------------------------- // -> slice() method slices a part of the string and returns it as a new string. const str = "heaven is a place on earth"; console.log(str.slice(11)); // prints: "place on earth" console.log(str.slice(-5)); // prints: "earth" console.log(str.slice(0,6)); // prints: "heaven" console.log(str.slice(-8,-6)); // prints: "on" console.log(str.slice()); // prints: "heaven is a place on earth" --------------------------- // -> split() method divides a given string into an ordered list of substrings and puts substrings into an array, and returns the array. The initial string is not changed. const str = "Human beings!"; console.log(str.split(" ")); // prints: ["Human", "beings!"] console.log(str.split("")); // prints: ["H", "u", "m", "a", "n", " ", "b", "e", "i", "n", "g", "s", "!"] console.log(str.split()); prints: ["Human beings!"] --------------------------- // -> substring() method returns the part of the string between given start and end indexes. // -> \ is an escape character in JS. Special characters (quotation marks, and \) can be written using \ in front of them so that they'll be perceived as normal characters. // -> \n is also an escape notation that adds a new line. const str = "I\'ll keep coming" console.log(str.substring(6,10)); // prints: "keep" console.log(str.substring(5)); // prints: "keep coming" const poem = "Burn bridges\nand dance naked\nwith your tribe\non the islands\nthat you make.\n-Atticus" console.log(poem); // prints: // Burn bridges // and dance naked // with your tribe // on the islands // that you make. // -Atticus --------------------------- // -> toUpperCase() method returns the string value converted to uppercase. (If it's not a string, it will be converted to a string in the process.) // -> toLowerCase() method returns the string value converted to lowercase. // -> toLocaleLowerCase() method converts the string value to lowercase with specified locale settings. // -> toLocaleUpperCase() method method converts the string to uppercase with specified locale settings. const str = "2 Red Foxes"; console.log(str.toUpperCase()); // prints: "2 RED FOXES" console.log(str.toLowerCase()); // prints: "2 red foxes" const city1 = 'İstanbul'; console.log(city1.toLocaleLowerCase('en-US')); // prints: "i̇stanbul" console.log(city1.toLocaleLowerCase('tr')); // prints: "istanbul" const city2 = 'istanbul'; console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('en-US')); // prints: "Istanbul" console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('tr')); // prints: "İstanbul" --------------------------- // -> toString() method returns a string version of a given value. const areaCode = 407; console.log(areaCode.toString(), typeof areaCode.toString(), typeof areaCode); // prints: "407" string number

-

2. Number:

Number is a data type that is used to represent integers and decimals.

Numbers can be used to make simple mathematical operations, such as addition (+), subtraction (-), multiplication (*) and division (/). There is also the exponential operator, which is symbolized by **. (Example: 2 ** 3 will be equal to 8.) There are other operators as well, such as the modulo operator, which is also known as the “remainder operator”. It takes the second operand and divides the first one with it, and returns the remainder that is left. A good way to use a modulo operator is to see if a given number is odd or even. (Use number % 2 for it.)

Examples for the modulo operator:

console.log(25 % 5); // prints 0 console.log(17 % 5); // prints 2 console.log(29 % 2); // prints 1 (odd number) console.log(32 % 2); // prints 0 (even number)

A small note: JS uses a fixed number of bits (to be more precise, 64 bits) to store a Number data. Given 64 binary digits, you can represent 2⁶⁴ of numbers. As numbers can be both negative and positive, one bit is always occupied with this data, leaving us with 63 bits to store the actual number. So integers smaller than 2⁶³ can be represented precisely. But here is another issue: the decimals. Decimals lose precision as many of them need more than 64 bits to store (think of π).

To sum up, we can treat whole numbers smaller than 2⁶³ as precise, but decimals (fractional numbers) should always be thought of as approximations rather than a precise value.

Also, if a number is not in the range that can be represented by 64 bits, its value will be Infinity or -Infinity, which are also considered as of type Number.

There is also the issue of precedence, if there are multiple operations to be taken care of, the order of precedence will be: (You can remember it by the acronym they form: PEMDAS)

Parenthesis > Exponents > Multiplication > Division > Addition > Subtraction

Other data types can be converted to numbers by using the

Number()function. If it’s a value that cannot be converted, it will return NaN (Not A Number). NaN is also of type Number but it doesn’t have a numeric value. NaN is also the only value in JS that is not equal to itself.85 === 85 85 === 85.0 Number("85") // returns the number 85 Number("Mordecai") // NaN Number(undefined) // NaN typeof NaN // "number" NaN == NaN //returns false 0 / 0 = NaN NaN + 3 = NaN // -0 is also a number in JS. Weird, but here it is: 0 === -0 // true // There is also -Infinity: 32 / -0 = -Infinity 32 / 0 = InfinitySome methods come built-in with every number. You can check them from the MDN docs, or writing

Number.prototypeto your chrome console, which will return you the Number prototype object.👉 Click to view built-in number methods cheatsheet

// -> Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER static property represents the biggest reliable integer JS can represent as a number. // -> JS can only reliably represent numbers between -(2⁵³ - 1) and 2⁵³ - 1. Numbers outside this range can't be compared correctly. Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER; // ↪ 9007199254740991 Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 1 === Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 2; // ↪ true // -> Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER static property represents the biggest reliable integer JS can represent as a number. Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER; // ↪ -9007199254740991 Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER - 1 === Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER - 2; // ↪ true //-> Number.isSafeInteger() determines if a given value is a safe integer or not. Number.isSafeInteger(10); // ↪ true Number.isSafeInteger(10.3); // ↪ false Number.isSafeInteger("10"); // ↪ false Number.isSafeInteger(Infinity); // ↪ false // -> Number.MAX_VALUE represents the biggest numeric value a number can hold, beyond this number lies infinity. Number.MAX_VALUE; // ↪ 1.7976931348623157e+308 Number.MAX_VALUE * 2; // ↪ Infinity // -> Number.MIN_VALUE represents the smallest number that is close to 0 and can be represented within float precision. // -> It is NOT the smallest negative number JS can represent. Number.MIN_VALUE; // ↪ 5e-324 Number.NaN; // represents NaN, same as NaN. Number.NEGATIVE_INFINITY; // represents -Infinity Number.POSITIVE_INFINITY; // represents +Infinity // -> Number.isFinite() determines if a given value is finite or not. Number.isFinite(1 / 0); // ↪ false Number.isFinite(22312 / 23); // ↪ true typeof 0 / 0; // NaN Number.isFinite(0 / 0); // ↪ false // -> Number.isInteger() determines if a given value is an integer or not. Number.isInteger(0); // ↪ true Number.isInteger(12); // ↪ true Number.isInteger(-12); // ↪ true Number.isInteger(0.3); // ↪ false Number.isInteger(NaN); // ↪ false Number.isInteger(Infinity || -Infinity); // ↪ false Number.isInteger("10"); // false Number.isInteger(true || false); // ↪ false Number.isInteger([1, "a"]); // false // -> Number.isNaN() determines if a given value is type of NaN or not. Number.isNaN(NaN && Number.NaN && 0 / 0); // ↪ true Number.isNaN(10 && "hello" && undefined && true && null); // ↪ false // -> Number.parseFloat(str) parses a floating point number from a given string. If it cannot be parsed, returns NaN. Number.parseFloat("7.65"); // ↪ 7.65 Number.parseFloat("hello world"); // ↪ NaN // -> Number.parseInt(str) parses an integer from a given string. If it cannot be parsed, returns NaN. Number.parseInt("9.99"); // ↪ 9 Number.parseInt("9.12"); // ↪ 9 Number.parseInt("-9.92"); // ↪ -9 Number.parseInt(""); // ↪ NaN Number.parseInt("hello"); // ↪ NaN // -> Number.prototype.toFixed() limits the floating point to a given number. let num = 12.3456789; num.toFixed(); // ↪ "12" num.toFixed(2); // ↪ "12.35" // Note the rounding! num.toFixed(5); // ↪ "12.34568" // Note the rounding! num.toFixed(9); // ↪ "12.345678900" // Note the 0's at the end! // -> Number.prototype.toLocaleString() returns a language specific implementation of a given string. let num = 123456789.0; num.toLocaleString("ar-EG"); // ↪ "١٢٣٬٤٥٦٬٧٨٩" // As a second argument you can give an optional argument that defines options num.toLocaleString("de-DE", { style: "currency", currency: "EUR" }); // ↪ "123.456.789,00 €" // -> Number.prototype.toString() returns a string value that represents the given number. You can give an optional base value as an argument. let num = 256; let float = 128.25; let negativeNum = -256; num.toString(); // ↪ "256" float.toString(); // ↪ "128.25" negativeNum.toString(); // ↪ "-256" num.toString(2); // ↪ "100000000" // base 2, binary num.toString(16); // ↪ "100" // base 16, hexadecimal // -> Number.prototype.valueOf() returns the numeric value of a number object. const numObject = new Number(123); typeof numObject; // ↪ "object" const numValue = numObject.valueOf(); // ↪ 123 typeof numValue; // ↪ "number"You can use three methods to convert a string to a number:

let num = "123"; // 1. Number(num); // ↪ 123 // 2. parseInt(num); // ↪ 123 // 3. console.log(+n); // ↪ 123

-

3. BigInt:

BigInt is the data type that is used for numbers that are larger than 2⁵³ - 1, which is the largest number that can be reliably represented with JavaScript Number data type. To indicate that a value is a BigInt type, you either append “n” to the end of the value or call the BigInt function.

Example:

typeof 198798700707039858n === "bigint"; // true typeof BigInt("198798700707039858") === "bigint"; // true typeof 1; // ↪ "number" typeof 1n; // ↪ "bigint" // A bigInt is not strictly equal to a Number 1n === 1; // ↪ false // but they are loosely equal 1n == 1; // ↪ trueNumber to BigInt coercion (or otherwise) is not recommended by MDN docs, as it can lead to a loss of precision.

-

4. Boolean:

There are only two boolean values: true or false. They are really useful for setting flags.

All values have an inherent truthy or falsy value under their real values. That means, in certain conditions, they will act like boolean values.

Everything else is truthy except falsy values! And here are the falsy values:

- False (oh, such a coincidence)

- 0

- "", ”, “ (empty string)

- null

- undefined

- NaN

-

5. Undefined: If a variable is declared and no value is assigned to it, its value is undefined. This is a value, but it is not a meaningful one as it carries no information. In JS, operations return the value of undefined, if they are not supposed to return some meaningful value.

let name; typeof name; // ↪ undefined

-

6. Null:

Null and undefined are very similar with a slight difference. They both mean nothing, but null has the connotation of being set specifically to nothing, while undefined has the connotation that that property has never been set at all. For a value to be null, a developer has to explicitly set it to null.

let name = null; typeof name; // ↪ null

-

7. Symbol:

Symbol data type was introduced to JavaScript in ES2015. They are a little confusing and they have very special use cases. The most valuable part of a symbol is its uniqueness. You create a symbol by using the

Symbol()keyword, and any argument it gets (which is also called the symbol name) is used for debugging purposes. It doesn’t affect anything. Even if you don’t provide any arguments, with each call, the Symbol keyword will create a unique symbol.Also, JavaScript does not automatically coerce symbols into strings, if you want strings, you gotta make them yourself.

// This is how you create a symbol: const bird = Symbol("Cookie"); console.log(typeof bird); // -> prints: symbol console.log(bird); // -> prints: Symbol(Cookie) console.log(bird.valueOf()); // -> prints: Symbol(Cookie) console.log(bird.toString()); // -> prints: "Symbol(Cookie)" console.log(bird.description); // -> prints: "Cookie" // Each created symbol is unique and immutable. console.log(Symbol("Cookie") === Symbol("Cookie")); // -> prints: false console.log(Symbol("Cookie") == Symbol("Cookie")); // -> prints: false // Symbols can be used to create private properties, to prevent accidental access or overwriting. // If you're working with a third-party API that provides you some sort of information, but you would like to add another key-value pair for your own use, creating keys as symbols will prevent third-party access. // This is our third party code: let player = { name: "Midoritori", species: "Night elf", occupation: "Monk", covenant: "Night Fae", mount: "Silky Shimmermoth", }; // Let's say that we want to add an id to this player: let id = Symbol(player.name); player[id] = 1; console.log(player[id]); // -> prints: 1 // To add them in object literal, you need to wrap the Symbol in square brackets: let id1 = Symbol("id"); let pet = { species: "parrot", name: "Cookie", [id1]: 12, }; console.log(pet[id1]); // -> prints: 12 // JavaScript keeps a global registry of all the Symbols created in that script. // If you want to read a specific symbols value, but if it doesn't exist, create one, you use Symbol.for(key): let id2 = Symbol.for("id"); let id3 = Symbol.for("id"); console.log(id1 === id2); // -> prints: false (for this to be true, we needed to create the id1 with Symbol.for(key) as well.) console.log(id2 === id3); // -> prints: true // You can also query the symbol name by using Symbol.keyFor(sym): console.log(Symbol.keyFor(id2)); // prints: "id"Symbols are not enumerated. You cannot use

for...in, orfor...of, or any other loop on them. They will also not show among the the properties of the object whenObject.getOwnPropertyNames()is used.JSON.stringifywill also omit the key-value pairs where the key is of type Symbol.let id1 = Symbol("id"); let pet = { species: "parrot", name: "Cookie", [id1]: 123, }; console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyNames(pet)); // -> prints: ["species", "name"] console.log(pet); // {species: "parrot", name: "Cookie", Symbol(id): 123} for (let key in pet) { console.log(`key: ${key}, value: ${pet[key]}`); } // -> prints: // key: species, value: parrot // key: name, value: CookieHowever, the symbols are not completely hidden: you can reach them by using

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(obj)static method.// I'm using the object in the example above: console.log(Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(pet)); // -> prints: [Symbol(id)]To sum up, symbols are mostly used for providing unique values. Their use cases, however, are somewhat a little miscellaneous.

Non-primitive (Reference) data types:

Arrays, Object Literals, Functions, Dates, and anything else…

In reference data types when you create a variable, the variable doesn’t actually hold a value, instead, it holds a pointer to that value. So when you copy a variable, it’s the pointer that gets copied, not the value itself.

So if you change the value, all the values of the variables that store a pointer to that value will change. Keep this in mind when you’re working with reference-type values!

Example:

let bird1 = { type: "parrotlet", name: "Cookie" }

let bird2 = { type: "parrotlet", name: "Cookie" }

bird1 === bird2 // false

{} === {} // falseNon-primitive data types are mutable, which means you can modify them on the go (unlike primitive values).

Example:

let pets = ["Cookie", "Dust", "Dander"];

pets[1] = "Cake";

console.log(pets); // ["Cookie", "Cake", "Dander"]-

1. Function:

We have seen many built-in functions up until this point, and we’ll keep on seeing them, but this is the time we talk about what functions are. Functions are reusable pieces of code that are designed to do certain tasks. Parentheses (()) that follow the ‘function’ keyword is the most basic way to indicate that a code block will serve as a function. The parentheses may or may not include arguments.

You have to first define what the function is going to be called and what it is supposed to do, and this is called the function declaration or the function statement. (The terminology related to this subject is sometimes used synonymously, and although they have some subtle differences, and I’m not exactly sure if they really matter when it comes to everyday programming. For example, function declarations are hoisted to the top of their closures while function expressions are not. This simply means that the declared functions can be used before they were defined, but that won’t work with expressed functions. But as common sense, isn’t it better to define functions before calling them anyway?)

Let’s create a function in three different ways:

// -> Function declaration: function double(num) { return num * 2; } // -> Function expression: const double = function d(num) { // Here, the inner function has a name that is 'd'. It can call itself and be recursive if it wants to. return num * 2; }; // If the inner function doesn't have a name, it will be an anonymous function, and it will look like this: (And it is totally fine if nothing else is referring to the inner function anyway.) const double = function (num) { // Here, the inner function doesn't have a name. return num * 2; }; // -> Arrow function expression: (Introduced with ES6, fairly new.) const double = (num) => { return num * 2; }; // Arrow functions can be simplified. If you have one argument, you can omit the parentheses and if you have a single line of code to execute, you can omit the curly braces and the return statement: const double = (num) => num * 2; // See how cute and simple this is?You can return or print something with a function, but you don’t have to. If you return nothing from it, it will simply return

undefined.Defining a function will not run that piece of code, it is merely a description. To execute that code, you need to invoke or call that function.

// -> Calling a function: double(2); // prints: 4 double(39); // prints: 78A declared function returns us an arguments object, which we can use if we like to.

function doesntMatter() { console.log(arguments); } doesntMatter(56, "hello", true); // prints: [56, "hello", true, callee: ƒ, Symbol(Symbol.iterator): ƒ] // The arguments.callee method contains currently executing function. // -> The arrow function has a slightly different syntax called the rest operator: const doesntMatter = (...args) => { console.log(args); }; doesntMatter(56, "hello", true); // prints: [56, "hello", true]Higher-order functions:

Higher-order functions are functions that either return a function or take a function as an argument. The function taken as an argument is also referred to as the callback function (cb). Many built-in methods such as setInterval, setTimeout, forEach, map, filter, reduce, and more are higher-order functions. You can see many of them with their examples in the

built-in array methodssection of this article.Let’s create a very simple higher order function ourselves:

function multiplier(n) { return (m) => m * n; } let multiplier2 = multiplier(2); let multiplier3 = multiplier(3); console.log(multiplier2(21)); // prints: 42 console.log(multiplier3(21)); // prints: 63The multiplier function above returns a function using a parameter, therefore it can be used as a custom function creator.

Built-in functions like

setInterval(cb, duration)andsetTimeout(cb, duration)are used to execute functions once in a while and after a duration of time, respectively. Duration is given as milliseconds.// setInterval pushes the given cb function to the call stack in every given miliseconds. setInterval(() => { console.log("Hello"); }, 1000); // setTimeout pushes the given cb function to the call stack after the specified miliseconds, only to be executed a single time. setTimeout(() => { console.log("What's up?"); }, 1000);

-

2. Object:

An object is an unordered data structure consisting of key-value pairs. Object keys can be either of type string or symbol and nothing else. If the value of a property is a function, that key-value pair is called a method, otherwise, keys are also known as the properties of an object.

// -> To create an object literal, wrap the key-value pairs in double curly braces: let obj = { shape: "rectangle", color: "black", sides: 6, }; console.log(obj); // prints: {shape: "rectangle", color: "black", sides: 6}Notice something weird? I have no quotation marks around the keys. The keys are directly converted to strings without me doing anything, so I can write them without quotation marks too.

// -> You can get the specific values by using either a dot or square brackets notation: console.log(obj.shape); // prints: rectangle console.log(obj["shape"]); // prints: rectangleThere’s a special keyword to indicate the properties of the object itself, and it is this keyword. (If you’re going to use ‘this’, don’t use the arrow function to define the method. ‘this’ in arrow functions refer to the surrounding function scope, which in this example is the window object.)

// Let's add a method to our object and use 'this' keyword as well: obj.ring = function () { console.log(`This ${this.color} ${this.shape} is ringing!`); }; console.log(obj); // prints: {shape: "rectangle", color: "black", sides: 6, ring: ƒ} obj.ring(); // This black rectangle is ringing!👉 Click to view built-in object methods cheatsheet

// -> Object.assign() is used to copy an object (without touching the original object) const obj = { color: "white", luckyNumbers: [12, 34, 56], }; const copyObj1 = Object.assign({}, obj); const copyObj2 = Object.assign({ hasAnotherProperty: true }, obj); console.log(copyObj1); // prints: {color: "white", luckyNumbers: Array(3)} console.log(copyObj2); // prints: {hasAnotherProperty: true, color: "white", luckyNumbers: Array(3)} // Object.create() method creates a new object by using another object as its prototype const artist = { name: "Leonardo", shout: function () { console.log(`I am ${this.name} and I love painting!`); }, }; const vincent = Object.create(artist); vincent.name = "Vincent van Gogh"; // you can override values vincent.age = 37; // you can add new properties vincent.shout(); // Prints: I am Vincent van Gogh and I love painting! // -> Object.keys() returns the keys of an object as an array // -> Object.values() returns the values of an object as an array // -> Object.entries() returns each key-value pair in their own array inside of another array (returns an array of arrays) const user = { name: "River Song", id: 12134343454356, }; console.log(Object.keys(user)); // prints: ["name", "id"] console.log(Object.values(user)); // prints: ["River Song", 12134343454356] console.log(Object.entries(user)); // prints: [["name", "River Song"], ["id", 12134343454356]] // -> Object.freeze() is used to freeze an object, which means preventing the addition of new properties and the modification of the existing ones. (So it means the existing properties are immutable.) It returns the same object that was passed to this function. // -> Object.isFrozen() determines if an object is frozen or not, returns a boolean value // -> Object.preventExtensions() prevents new properties from being added to an object // -> Object.isExtensible() determines if we can add new properties to an object, returns a boolean value const anyObj = { isCute: true, color: "purple", }; Object.freeze(anyObj); anyObj.isCute = false; // Cannot modify existing properties: Throws an error in strict mode anyObj.age = 3; // Cannot add any new properties: Throws an error in strict mode console.log(anyObj.isCute); // Prints: true console.log(anyObj.age); // Prints: undefined console.log(Object.isFrozen(anyObj)); // Prints: true console.log(Object.isExtensible(anyObj)); // Prints: false // -> Object.seal() is used to prevent the addition of new properties, but doesn't prevent the modification of the existing ones: // -> Object.isSealed() determines if an object is sealed or not, returns a boolean value const newObj = { isRound: true, name: "Bubbles", }; Object.seal(newObj); newObj.isRound = false; // No errors newObj.age = 3; // Cannot add any new properties: Throws an error in strict mode console.log(newObj.isRound); // Prints: false console.log(newObj.age); // Prints: undefined console.log(Object.isSealed(newObj)); // Prints: true console.log(Object.isExtensible(newObj)); // Prints: false // -> Object.hasOwnProperty() checks if a given object has a specified property and returns a boolean value. Inherited properties return false const anotherObj = { id: 123456789 }; console.log(anotherObj.hasOwnProperty("id")); // Prints: true console.log(anotherObj.hasOwnProperty("hasOwnProperty")); // Prints: false // -> Object.is() determines if two given values are the same, returns a boolean value const obj = { id: 1 }; console.log(Object.is(1, 1)); // Prints: true console.log(Object.is(true, "true")); // Prints: false console.log(Object.is({ id: 1 }, { id: 1 })); // Prints: false console.log(Object.is(obj, obj)); // Prints: true console.log(Object.is([], [])); // Prints: false console.log(Object.is(0, +0)); // Prints: true console.log(Object.is(-0, +0)); // Prints: false console.log(Object.is(null, undefined)); // Prints: false -

3. Array:

An array is an ordered data structure consisting of values and each value has an index number that corresponds to it. They also have a length property just like strings.

👉 Click to view built-in array methods cheatsheet

// -> Array.from() static method creates a new array of a given iterable object. You can use an optional second argument to map the iterable value. console.log(Array.from(123)); // prints: [], numbers are not iterable! console.log(Array.from("sauce")); // prints: ["s", "a", "u", "c", "e"], strings are iterable! console.log(Array.from([1,2,3], x => x+3)); prints: [4, 5, 6] --------------------------- // -> Array.isArray() static method determines if a given value is an array or not. Array.isArray([1, 2, 3]); // true Array.isArray({name: "Elisa"}); // false Array.isArray('Elisa'); // false Array.isArray(undefined); // false Array.isArray(null); // false --------------------------- // -> Array.of() static method creates an array from any given value. Array.of(78); // [78] Array.of(1, 2, 3); // [1, 2, 3] Array.of("sauce", "apple"); // ["sauce", "apple"] Array(8); // creates an empty array with the length property of 8. --------------------------- // -> concat() method merges two or more arrays and returns the result as a new array. // -> join() method merges the elements of an array with a given separator and returns the result as a string. // -> toString() method merges the elements of an array with a comma between them and returns the result as a string. const arr1 = ["Sir", "Nicholas"]; const arr2 = ['C', 'a', 't']; const arr3 = arr1.concat(arr2); console.log(arr3); // prints: ["Sir", "Nicholas", "C", "a", "t"] console.log(arr3.join()); // prints: Sir,Nicholas,C,a,t console.log(arr3.toString()) // prints: Sir,Nicholas,C,a,t console.log(arr3.join("")); // prints: SirNicholasCat console.log(arr3.join(" ")); // prints: Sir Nicholas C a t --------------------------- // -> slice(start, end) method slices the arrays from given start and end indexes and returns it as a new array. It does not mutate the original array. If an end index is not given, it will start from the given start index and slice // -> splice() method is used to remove or replace some amount of contents in a given array. It mutates the original array, so use it with caution. It will return the removed items as an array. const arr = ["cat", "dog", "parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] console.log(arr.slice()) // Prints: ["cat", "dog", "parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] console.log(arr.slice(2,4)) // Prints: ["parrot", "dragon"] console.log(arr.slice(2)) // Prints: ["parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] console.log(arr) // Prints: ["cat", "dog", "parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] arr.splice(2, 0, "dinosaur") // Delete 0 items starting with index 2 and add "dinosaur" before index 2. Returns [] console.log(arr) // Prints: ["cat", "dog", "dinosaur", "parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] arr.splice(1, 1) // Delete 1 item starting with index 1. Returns ["dog"] console.log(arr) // Prints: ["cat", "dinosaur", "parrot", "dragon", "monkey"] arr.splice(3, 2, "wolf", "fox") // Delete 2 items starting with index 3 and add the given values to the same space. Returns ["dragon", "monkey"] console.log(arr) // Prints: ["cat", "dinosaur", "parrot", "wolf", "fox"] --------------------------- // -> entries() method returns an Array Iterator object that contains key-value pairs for each item on that given array. const arr = ['a', 'b', 'c']; const iterator = arr.entries(); console.log(iterator.next().value); // prints: Array [0, "a"] for(let [index, element] of iterator) { console.log(index, element); } // prints: 0 "a" 1 "b" 2 "c" --------------------------- // -> every() method tests whether every item in a given array passes the test by a given function, and returns a boolean value in the end. // every method on an empty array will return true for any condition. const isOver21 = age => age >= 21; const arr = [26, 29, 30, 32]; console.log(arr.every(isOver21)); // prints: true --------------------------- // -> fill(value, start, end) method replaces values with another value, from a start index (default 0) to an end index (default array.length). It returns the modified array. // fill is a mutator method, it will change the array. const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]; console.log(arr.fill(0, 2, 4)); // prints: [1, 2, 0, 0, 5, 6] console.log(arr.fill("hello", 3)); // prints: [1, 2, 0, "hello", "hello", "hello"] console.log(array1.fill(6)); // prints: [6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6] console.log(array1); // prints: [6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6] --------------------------- // filter() method takes a callback function and calls that callback function for every item in the array, constructs a new array of the values that returns true, and returns this new array. // filter() is NOT a mutator method, it will return a new array without touching the given one. const words = ['camp', 'marshmallow', 'tent', 'firewood', 'mountain', 'bag']; const result = words.filter(word => word.length >= 5); console.log(result); // prints: Array ['marshmallow', 'firewood', 'mountain'] console.log(words); // prints: ['camp', 'marshmallow', 'tent', 'firewood', 'mountain', 'bag']; --------------------------- // -> find() method returns the value of the first element in the given array that satisfies the testing function provided by the callback function. // -> findIndex() method does the same thing, but instead of the value, it returns the index. const words = ['camp', 'marshmallow', 'tent', 'firewood', 'mountain', 'bag']; const found = words.find(el => el.length > 7); const foundNum = words.findIndex(el => el.length > 7); console.log(found); // prints: 'marshmallow' console.log(foundNum); // prints: 1 --------------------------- // -> indexOf() method returns the index of the first value that matches a given value. If the given value doesn't exist in the array, it will return -1. // -> lastIndexOf() method returns the last index at which a given element is found by searching the array from backwards. If the given value doesn't exist in the array, it will return -1. // -> includes() method determines if a given value exists in an array, returns a boolean value. As a second argument, it can take a starting index. The algorithm searches the array from start to finish. // -> some() method checks if at least one element of a given array passes a given condition. It takes a callback function as an argument. const words = ['camp', 'marshmallow', 'tent', 'tent', 'firewood', 'mountain', 'tent', 'bag']; console.log(words.indexOf('tent')); // prints: 2 console.log(words.indexOf('blabber')); // prints: -1 console.log(words.indexOf()); // prints: -1 console.log(words.lastIndexOf("tent")) // prints: 6 console.log(words.lastIndexOf("tent", 5)) // In Latin: Look for a "tent", but instead of starting the search from the last index, start from index 5. Prints: 3 console.log(words.lastIndexOf("sunscreen")) // prints: -1 console.log(words.includes("bear")) // prints: false console.log(words.includes("bag")) // prints: true console.log(words.includes("bag", -1)) // prints: true console.log(words.includes("bag", 2)) // prints: true console.log(words.includes("bag", 50)) // prints: false console.log(words.some(el => el.length > 6)) // prints: true console.log(words.some(el => el.length < 3)) // prints: false --------------------------- // -> pop() method removes the last element of a given array and returns the removed element // -> push() method adds one or more elements to the end of a given array and returns the length of the final array // -> shift() method removes the first element of a given array and returns the removed element // -> unshift() methods adds one or more elements to the beginning of a given array and returns the length of the final array const veggies = ["broccoli", "kale", "carrot"] console.log(veggies.push("spinach", "cauliflower")) // Prints: 5 console.log(veggies.unshift("asparagus", "cabbage")) // Prints: 7 console.log(veggies) // Prints: ["asparagus", "cabbage", "broccoli", "kale", "carrot", "spinach", "cauliflower"] console.log(veggies.pop()) // Prints: "cauliflower" console.log(veggies.shift()) // Prints: "asparagus" console.log(veggies) // Prints: ["cabbage", "broccoli", "kale", "carrot", "spinach"] --------------------------- // -> forEach() method executes a provided function for each element of a given array const arr = ["sunshine", 22, 'bird']; arr.forEach(el => console.log(el)); // prints: sunshine 22 bird --------------------------- // -> map() method takes a function as an argument, applies that function to each element of a given array, and creates and returns an array populated with the results of each equation. It can get an optional second argument which denotes the index number, and a third one to denote the array that this method was called upon. If you're not using the returned array, then it is better to use the forEach method or the for...of loop. // -> flat() method creates a new array with sub-array elements using the specified depth // -> flatMap() applies a callback function to a given array, then flattens the array one level. It is actually the same as using map() and flat(1) consecutively. const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] const mappedArr = arr.map((el, index, arr) => el ** arr[index]) // arr[index] is actually el itself, so this was done for the example's sake :] console.log(mappedArr) // Prints: [1, 4, 27, 256, 3125] const nestedArr = [[1, 2], [3, 4, [5, 6, 7]], 8] console.log(nestedArr.flat(1)) // Flattened one level depth, prints: [1, 2, 3, 4, [5, 6, 7], 8] console.log(nestedArr.flat(2)) // Flattened two level depth, prints: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] console.log(nestedArr) // Original array stays the same, prints: [[1, 2], [3, 4, [5, 6, 7]], 8] console.log(arr.map(el => [el * 2])) // prints: [[2], [4], [6], [8], [10]] console.log(arr.flatMap(el => [el * 2])) // prints: [2, 4, 6, 8, 10] --------------------------- // -> reverse() method reverses an array and returns the new array // -> sort() sorts the given array in ascending order and returns the sorted array. The algorithm converts the elements to strings and compares their UTF-16 code unit values. The time and space complexity of the algorithm changes in between browsers as it depends on implementation details. It can take an optional function argument that defines the comparing parameters, that can reverse the order from ascending to descending. // Both of these functions change the original array, so be careful when using them. const numArr = [1, 12, 53, 9, 47, 17] const strArr = ["a", "fl", "cr", "xp", "ei"] const mixedArr = [1, 12, "cat", 9, 47, "dog"] console.log(numArr.reverse()) // prints: [17, 47, 9, 53, 12, 1] console.log(numArr) // prints: [17, 47, 9, 53, 12, 1] numArr.sort() // In numeric sort, as the characters are converted to strings, other characters come before "9" because that's the Unicode order of strings. strArr.sort() mixedArr.sort() console.log(numArr) // prints: [1, 12, 17, 47, 53, 9] console.log(strArr) // sorts in alphabetical order, prints: ["a", "cr", "ei", "fl", "xp"] console.log(mixedArr) // first sorts numbers then strings, prints: [1, 12, 47, 9, "cat", "dog"] console.log(numArr.sort((a,b)=> a-b)) // prints: [1, 9, 12, 17, 47, 53] console.log(numArr.sort((a,b)=> b-a)) // prints: [53, 47, 17, 12, 9, 1] --------------------------- // -> reduce() method executes a specified function on each element of a given array, returns the result as a single value. The specified function has 2 required (accumulator, currentValue) and 2 optional (currentIndex and array) parameters. It can take an initial value as a second argument. If no initial value is supplied, the first element in the given array is used as the accumulator value. // -> reduceRight() does the same thing as reduce, but in the opposite direction, from right to left. const arr = [10, 20, 30, 40]; console.log(arr.reduce((accumulator, currentValue, currentIndex, array) => accumulator * currentValue)); // 10 * 20 * 30 * 40, prints: 240000 console.log(arr.reduce((accumulator, currentValue) => accumulator * currentValue, 2)); // 2 * 10 * 20 * 30 * 40, prints: 480000 console.log(arr.reduce((acc, currVal)=> acc.toString() + (currVal))) // prints: 10203040 console.log(arr.reduceRight((acc, currVal)=> acc.toString() + (currVal))) // prints: 40302010

-

4. Date:

The built-in JavaScript Date object has a variety of properties and methods which are very useful. Dealing with dates, however, is not always so easy.

To get the current time as a string, we can do two things:

console.log(Date()); // Prints a string with the current time console.log(new Date().toString()); // Prints the same string as above :]To create a date for a specific time, you can pass arguments:

let birthday = new Date(1994, 10, 9); // Month is 0-indexed. console.log(birthday); // Prints: "Wed Nov 09 1994 00:00:00 GMT-0500 (Eastern Standard Time)" let event = new Date("August 29, 1987 23:07:30"); console.log(event); // Prints: "Sat Aug 29 1987 23:07:30 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)"To get a piece of the date string that is created by using the Date object as a constructor, there are specified methods:

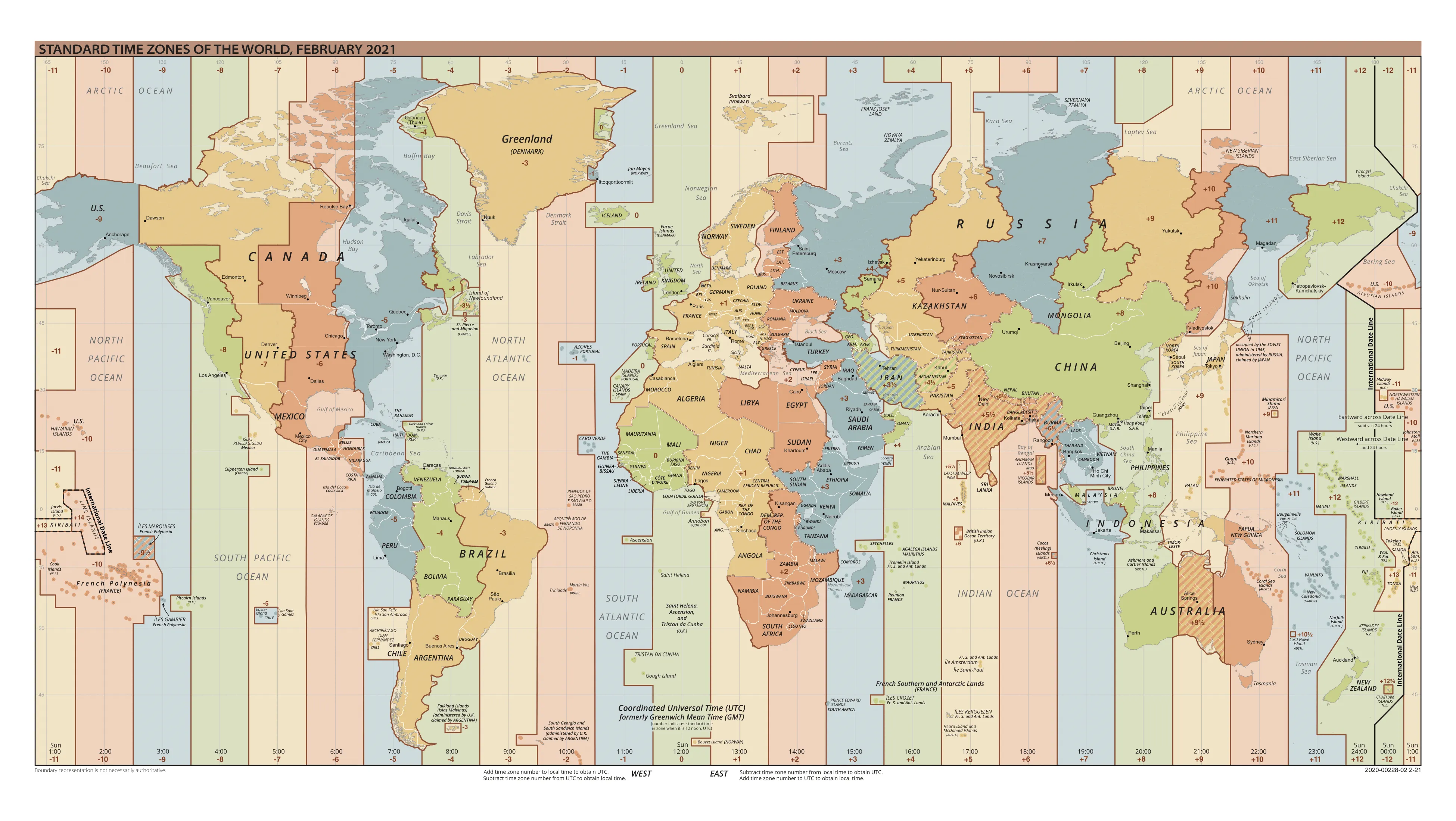

// To make sure we are looking at the same date, let's create a specific one: const date = new Date(2019, 04, 06, 23, 45, 30); console.log(date); // Prints: Mon May 06 2019 23:45:30 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) console.log(date.getFullYear()); // Prints: 2019 (Returns a 4-digit number) console.log(date.getMonth()); // Prints: 4 (Months are 0-indexed, this will return a number between 0-11 at all times.) console.log(date.getDate()); // Prints: 6 (Returns a number between 1-31) console.log(date.getHours()); // Prints: 23 (Returns a number between 0-23) console.log(date.getMinutes()); // Prints: 45 (Returns a number between 0-59) console.log(date.getSeconds()); // Prints: 30 (Returns a number between 0-59) console.log(date.getMilliseconds()); // Prints: 0 (Returns a number between 0-999) console.log(date.getTime()); // Prints: 1557200730000 (Returns the miliseconds that has passed since January 1, 1970) console.log(date.getDay()); // Prints: 1 (Returns the weekday as a number, 0-indexed, expect something between 0-6. Weekdays start with sunday, not monday.)To get a time standard we use UTC, which is short for Coordinated Universal Time. UTC is a successor for GMT, which stands for Greenwich Mean Time. (GMT = UTC±00:00) For anything international, we try to avoid using locale dates. Not using standards in international settings may result in massive losses of time, money, and energy, such as this one. UTC is used in aviation, air traffic control, flight plans, weather forecasts, and the International Space Station (ISS). It is also used by the Network Time Protocol, which is the system that is designed to synchronize the clocks of electronic devices that are connected to the internet. Timezones are expressed by using positive or negative offsets from UTC (e.g. UTC+01:00). Some countries have multiple timezones. For example, France has 12 timezones that range between UTC-10 to UTC+12 and is the country that has the most amount of timezones in the world. Check out this map of the world timezones:

Map of current official time zones. Click on the following link if you’d like to see a bigger image. Image Credit: TimeZonesBoy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/World_Time_Zones_Map.png

// -> Date.UTC() accepts the same parameters as the Date constructor, but treats them as UTC time: // Has to have at least two arguments! const utcDate = new Date(Date.UTC(96, 1, 2)); console.log(utcDate); // Thu Feb 01 1996 19:00:00 GMT-0500 (Eastern Standard Time) console.log(utcDate.toUTCString()); // "Fri, 02 Feb 1996 00:00:00 GMT" // UTC also has several other methods, such as setUTCDate(),setUTCMonth(), setUTCFullYear, etc.To get a language-sensitive representation of a given date, you can use the

toLocaleString()method. The first argument is a string that specifies the language and the country (some countries speak multiple languages and have multiple standards), and the second argument is an options object. The first argument is composed of two parts divided by a dash, the first half being the ISO-639 language code, the second half being the ISO-3166 country code. You can check this website for available codes.const event = new Date(Date.UTC(2018, 8, 23, 14, 30, 30)); // UK Locale: console.log(event.toLocaleString("en-GB", { timeZone: "UTC" })); // Prints: 23/09/2018, 14:30:30 // Japan Locale: console.log(event.toLocaleString("ja-JP", { timeZone: "UTC" })); // Prints: 2018/9/23 14:30:30 // Korea Locale: console.log(event.toLocaleString("ko-KR", { timeZone: "UTC" })); // Prints: 2018. 9. 23. 오후 2:30:30There are many properties and methods of the date object and I encourage you to check them from MDN Docs as well.

Logical Operators

JS supports four logical operators, OR(||), AND(&&), NOT(!) and NULLISH COALESCING(??).

// NOT(!) is a unary operator and flips the value to the opposite when used.

console.log(!false); // prints: true

// AND(&&) will return true only if both of the given values are true.

console.log(!false && true); // prints: true

console.log(!false && !true); // prints: false

// OR(||) will return true if at least one of the given values are true.

console.log(true || true); // prints: true

console.log(false || true); // prints: true

console.log(false || false); // prints: false

// Nullish Coalescing(??) will return the rightside value only if the left side is either null or undefined.

// Otherwise, it will return the leftside value.

console.log(null ?? { name: "Barusu" }); // prints: {"name": "Barusu"}

console.log(undefined ?? { name: "Barusu" }); // prints: {"name": "Barusu"}

console.log(0 ?? { name: "Barusu" }); // prints: 0

console.log("" ?? { name: "Barusu" }); // prints: ""

console.log(["red", "apple", 12, false] ?? { name: "Barusu" }); // prints: ["red", "apple", 12, false]Precedence: || has the lowest precedence, followed by &&, comparison operators (>, <, >=, <=, ==, ===), which is also followed by the arithmetic operators (PEMDAS), respectively. ! has the highest precedence.

Peculiar behavior of logical operators:

The logical operators && and || handle things differently when they are given values of different types.

OR(||) operator checks the left-side value first. If it is true or truthy, it will directly return the first value. If the left-side value is false or falsy, it returns the right-side value.

console.log("hello" || null); // prints: "hello"

console.log(0 || "world"); // prints: "world"

console.log("!" || 2328); // prints: "!"

console.log(NaN || undefined); // prints: undefinedAND(&&) operator works differently. It also checks the left-side value first, if it is false or falsy, it directly returns the left-side value. If the left-side value is true or truthy, it returns the right-side value.

console.log("hello" && null); // prints: null

console.log(0 && "world"); // prints: 0

console.log("!" && 2328); // prints: 2328

console.log(NaN && undefined); // prints: NaNBoth of them have the same logic to it: They don’t check the value on the right side unless they have to. An || operator will result with true if the left-side value is true or truthy, and in this case, the right-side value doesn’t matter, so it is short-circuited. The same goes for the && operator, if the left-side value is false or falsy, the result will be false no matter what the right-side value is, so it is never evaluated.

Ternary Operator:

We have seen unary and binary operators, but there is also a ternary operator, which is also known as the conditional operator. The unary operator operates on a single value, the binary operator operates on two values, and the ternary operator operates on three values. For the syntax, a question mark (?) and a colon (:) is used. Statement before the question mark indicates condition, the statement after that is what will happen if that condition is true, and the statement after the colon is what happens if that condition isn’t met.

let status = "offline";

// Written with if-else:

let color;

if (status === "offline") {

color = "red";

} else {

color = "green";

}

// Written with ternary:

let color = status === "offline" ? "red" : "green";Type Coercion

Sometimes, JS automatically converts one type to another, especially if an operation is taking place. This is called the type coercion.

// Null gets converted to 0 when used with mathematical operations:

console.log(null * 10); // Prints: 0

console.log(null + 10); // Prints: 0

// Strings can be converted to number when used with mathematical operations:

console.log("12" - 1); // Prints: 11

console.log("12" * 2); // Prints: 24

// Numbers get converted to strings if used with +:

console.log("12" + 34); // Prints: 1234

console.log(12 + "aa"); // Prints: 12aa

// Strings can be converted to NaN when used with mathematical operations:

console.log("eightynine" - 1); // Prints: NaNThere are two types of comparison operators, one is the double equals(==), which tests loose equality, the other one is triple equals(===), which tests for strict equality. Double equals perform type coercion, but triple equals don’t. Triple equals compare both value and data type, but double equals just check for value.

console.log(8 == "8"); // Prints: true

console.log(8 === "8"); // Prints: false

console.log(undefined == null); // Prints: true

console.log(undefined === null); // Prints: false

console.log(false == 0); // Prints: true

console.log(0 == ""); // Prints: true

console.log(NaN == NaN); // Prints: falseAs it behaves loosely and sometimes yields unexpected results, double equals operator is not much liked by the community. It is strongly recommended to use triple equals for comparison purposes.

I hate the endings, but here we are

If a new programmer is reading this, keep rocking on! If you don’t understand things, guess what, you’re just human. There are always cool people who’ll help you understand things. And if you keep trying to learn things, one day you’ll become a member of that cool and unique club, so keep on going on.

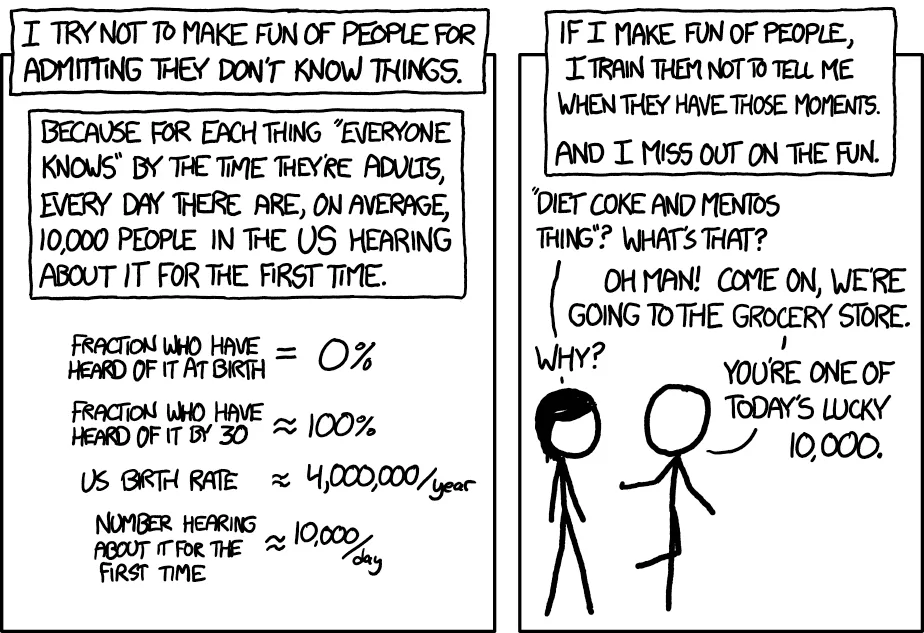

Image Credit: xkcd, https://xkcd.com/1053/

Don’t miss out all the fun!